ARCHIVE FILE

This article was published in 1997

See the original document

Reproduction by Nutrition Interactions: implications for the management of ewes and cows

GN Hinch, Department of Animal Science, University of New England, Armidale, NSW

Introduction

The nutrition of the reproducing female is possibly the major variable that can be altered through management on most Australian farms and this area of interest has been a central issue for research at UNE for a number of years. This paper will outline some of the major affects which nutrition can have at various phases of the reproduction cycle namely: ovulation, embryo implantation, foetal growth and lactation. Examples from Merino and crossbred ewe flocks will be used but reference will be made to cattle where data are available to support generalisations across both species. Details on the mechanisms of many of the interactions between reproduction and nutrition can be found in a excellent review by Robinson (1990).

Ovulation Rate

The maximisation or possible optimisation of ovulation rate at joining has been the subject of ongoing research for at least two decades in Australia and we now have a clear picture of how nutrition can be used to manipulate ovulation rate.

The static effect of live weight is well known and can be simply defined as a 2% increase in ovulation rate per kg live weight gain. Therefore an increase in average flock weight from 40 to 50kg at mating will increase the number of eggs shed in a Merino flock from about 1.1 to 1.3. This effect is consistent across most breeds although not clearly so for the high fecundity breeds such as Finn and Booroola.

The flushing effect of feeding (dynamic) on ovulation rate can be consistently obtained by feeding high levels of protein/energy rich food for short periods during the follicular phase of the oestrous cycle. Traditionally this has been achieved using lupins (approx 600 g/h/day) for as little as 4 days prior to the withdrawal of progesterone pessaries. The data in Table 1 show the results from a number of years of flushing experiments using Merino ewes given 600g/h/d of lupins. No weight differences were evident between control and lupin fed groups in any of the experiments. Similar responses have also been gained from the use of sunflower and cottonseed meals at similar levels of intake.

Although increases of around 20% are common the use of flushing is not recommend unless an improved nutritional regime post mating is introduced to ensure that the body condition of ewes is restored to levels which will assist in the later rearing of litters of more than one.

Table 1 Mean Ovulation rates of Merino ewes after Lupin feeding for 4 days prior to sponge withdrawal (Hinch unpublished)

| Experiment | Lupins | Control |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Fine wool | 1.61 | 1.25 |

| 2 Fine wool | 1.52 | 1.15 |

| 3 Medium Peppin | 1.42 | 1.09 |

| 4 Medium Peppin | 1.58 | 1.35 |

In cattle ovulation rate is of importance in determining the number of cows cycling. In recent years a number of studies at UNE have examined this issue in the context of improving the success rate of artificial insemination programs in Bos taurus cows. As might be expected the major issue is body weight / condition; cows with condition scores of less than 3.5 having poor conception rates and a large proportion do not show oestrus even after use of progestagen based synchronisation programs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effects of body condition on cow reproduction

Some recent collaborative work with NSW Agriculture (Wilkins pers. comm.) has shown that nutritional manipulations (flushing) can be used to induce cows to commence cycling and to improve conception rates. A thesis study (Nguyen 1996) indicated that supplementation of lactating cows with a lipid rich supplement (Rumentek) increased conception rates to AI by 14% (Table 2).

Table 2. The effects of protected lipid supplements (Rumentek 1kg/h/d) 2 weeks prior to mating on cow reproductive performance (Nguyen 1996)

| Response | Control | Rumentek | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum interval (d) | 67.8 | 68.6 | |

| Average Condition Score post treatment | 4.38 | 4.39 | |

| % in Oestrus after Synchronisation | 80.0 | 91.9 | |

| Conception to AI % | 46.4 | 60.8 | |

| Non-return rate % | 63.0 | 79.0 | |

| No Cows | 70 | 74 |

| Measure | Lupin fed (500g/h/d) | Control (oats—500g/h/d) |

|---|---|---|

| Ovulation rate | 1.37 | 1.22 |

| % returns to service | 7.5 | 0.9 |

| % partial embryo loss | 61 | 39 |

Studies on stress effects on embryo loss have also been conducted over a number of years. These studies arose as a result of the anecdotal comments that artificial insemination success in sheep was very much dependant on avoiding stress at and in the week following insemination. A number of experiments have been conducted to examine the effects of stressors including sub-maintenance nutrition, heat and parasitism on embryo loss. Generally the ewes have been stimulated with PMSG to increase ovulation rates slightly.

The evidence as illustrated in Table 4 is that stress at mating time can increase embryo loss; the mechanisms apparently differing with the form of the stressor. ACTH is certainly involved and it would appear that excessive levels during the early stages of development of the corpus luteum (days 1-3 post oestrus) can result in large losses of embryos due to a suppression of peak progesterone levels (Figure 2) an effect not induced by dexarnethasone.

Table 4. Embryo loss associated with Heat stress (40C for 6 hours/day for 7 days) in ewes immediately post AI (Hinch unpublished).

| Measure | Stressed ewes | Control ewes | ACTH immunised ewes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conception rate % | 64.0 | 83.3 | 82.7 |

| Embryo loss/ewe | 2.0 | 1.13 | 1.09 |

| Progesterone (ng/ml) | 9.94 | 9.62 | 9.49 |

| Ovulation rate | 2.36 | 2.25 | 2.24 |

Pregnancy

Other studies on embryo loss have been associated with an examination of the influence of embryo loss in high fecundity ewes on birth weights of surviving lambs. Data from a large number of high fecundity (Booroola cross) animals were used to demonstrate that embryo "wastage" was detrimental to birth weights (Hinch et al. 1986). Table 5 illustrates the effect with birth weight declining for litter sizes 1-4 born from litters losing 0, 1 or 2 embryosi.e.. ovulation rates from 1-6.

Figure 2. ACTH, Dexamethasone and Control treatments: Effects on progesterone levels throughout a ewe oestrous cycle.

Table 5 Pregnancy wastage effects on birth weights (kg) of lambs from High fecundity flocks (estimated survival %) (Hinch etal 1986).

| Littersize | Preg Wastage 0 | Preg Wastage 1 | Preg Wastage 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.67(98%) | 4.51(96%) | 4.41(94%) |

| 2 | 3.74(82%) | 3.58(80%) | 3.48(77%) |

| 3 | 2.98(65%) | 2.82(63%) | 2.70(60%) |

| 4 | 2.45(41%) | 2.29(37%) | 2.19(35%) |

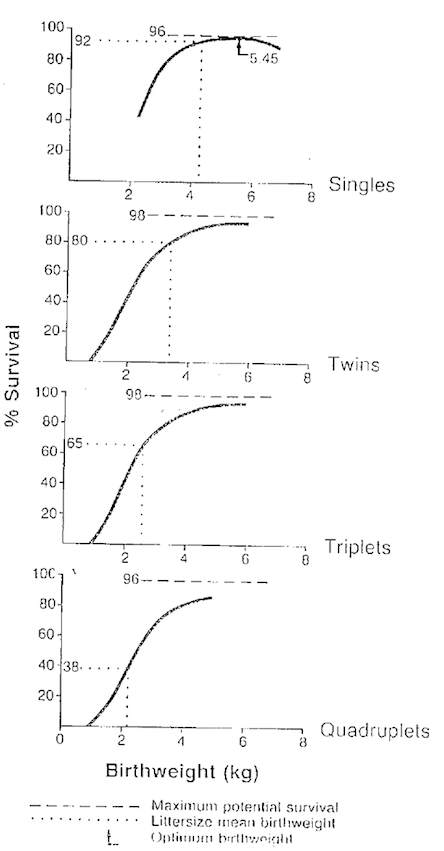

Associated with our interest in high fecundity flocks has been the nutritional management of these flocks to increase lamb survival levels. The initial concept was that this could be most easily done via manipulation of birth weight (the relationship of birth weight and survival for various litter sizes had been previously defined (Hinch etal 1985, Figure 3). A series of studies were initiated to examine specific protein supplementation regimes which maybe able to improve placental size and function and consequently birth weight of litters of >2 and also possibly colostrum production.

Breed differences and maternal reserves were also considered as previous studies had already indicated that ewes with condition scores of less than 2 (at day 120) partition energy to body gain rather than foetal growth in late pregnancy; a similar situation also occurs in growing maiden ewes. Ewes with fat scores of >3.5 in late pregnancy were also known to be likely to have reduced appetites and be more prone to pregnancy toxaemia.

The nutrition studies initially concentrated on protected protein supplementation aimed at increasing placental size in litters. Table 6 shows an experiment (Hinch unpublished) where protected casein was fed to crossbred ewes (carrying 2 or 3 lambs) from day 50 of pregnancy with the animals slaughtered at 110 days. The addition of 80 g/h/day of protected protein was enough to increase caruncle and placentome weights, protein above this appeared to increase foetal weight. A further study (Meyer and Hindi unpublished, Table 7) used 80g/h/day of cottonseed pellets over the same stage of pregnancy in Booroola Merino ewes. Again the protein supplement increased placentome weight and also mean litter weights at 90, 126 and 132 days of pregnancy. In both experiments the basal feed was poor quality dry feed typical of late winter in New England.Table 6. The influence of protected casein protein fed at 50-100 days of pregnancy on conceptus weights of high fecundity crossbred ewes (Hinch unpublished).

| Protein Level(g) | 0 | 80 | 160 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caruncle Wt (g) | 90 | 105 | 98 |

| Placentome (g) | 302 | 425 | 427 |

| Foetal Wt (g) | 1580 | 1477 | 1723 |

| Fat % | 2.11 | 1.74 | 1.79 |

Figure 3. Birth weight and survival relationships in high fecundity sheep.

Table 7. The influence of cottonseed meal (80g/h/d) fed during 50-100 days of pregnancy on conceptus weights of high fecundity Merino ewes (Meyer and Hinch unpublished).

| Cottonseed meal | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Placentome Wt (g) | 677 | 659 |

| Foetal Wt (90days) | 1449 | 1337 |

| Foetal Wt (126 days) | 7166 | 7053 |

| Foetal Wt (132 days) | 8663 | 8551 |

The importance of protein supplementation was further tested in a large scale trial (2 years) on 200 Border Leicester Merino ewes carrying 1,2,3 lambs (Hinch et al. 1996). Supplementation in mid and late pregnancy (80-120 g/h/d of cotton seed pellets) resulted in no significant differences in birth weights but did significantly improve survival of lambs from all litter sizes (Figure 4) implying that mechanisms other than just birth weight are important. The protein supplementation in this experiment had minimal effects on wool characteristics (weight and strength).

Figure 4. Cottonseed supplementation and Lamb birth weight and survival.

The issue of feeding to regulate birth weight in heifers is worthy of comment here. If we believe that birth weight has a genetic maximum then normally high energy intake will not allow this weight to be exceeded but rather additional energy will he partitioned to body fat which in turn may increase the incidence of difficult births (a subject of an experiment during this coming winter) via mechanisms other than excessive foetal size. To some degree the fact that protein supplementation used by Hinch et al. (1996) did not increase birth weight of single lambs in well fed ewes would support this concept. Studies with heifers would also support the concept. Nutritional restrictions from day 90 of pregnancy (resulting in a 20% weight loss) have only small effects on birth weight (3kg) and there is good evidence that energy is partitioned to the heifer's body rather than to the foetus (Koong etal 1982, Warrington etal 1988). Therefore it would seem that a strategy to feed adequate levels in late pregnancy to maintain foetal growth while trying to avoid over fatness by excessive nutrition is possibly a good policy. It may also be beneficial to avoid excessive nutrition during mid pregnancy although this requires further confirmation.

Lactation

As implied in the protein supplementation experiment factors other than birth weight may be involved in improved lamb survival. A study by Tiddy et al. (unpublished) has shown that supplementation of ewes in late pregnancy with protein (cottonseed meal 80g/h/d) results in large increases in the size of the mammary gland at parturition and in the amount of colostrum present (Table 8).

Table 8. Mammary weight and visible colostrum in dissected mammary glands from crossbred ewes at day 146 of gestation after late pregnancy supplementation with cottonseed meal (80g/h/d). (Tiddy et al. unpublished)

| Littersize | Supplement | Mammary Wt (g) | Colostrum Score* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 0 | 650 | 1.0 |

| 80 | 1290 | 1.2 | |

| Twin | 0 | 1210 | 1.7 |

| 80 | 1570 | 2.5 |

* Score 0-3 0 = no visible colostrum 3 = visible colostrum in all parts of gland

Further studies using late pregnancy supplementation with protein have confirmed these effects and have also shown positive effects on milk production in the first weeks of lactation - an effect apparently independent of body condition. These effects ave been observed in both cattle (Rustomo et al. 1996) and sheep. Figures 5 & 6 illustrate the impact of lupin supplementation (200 g/h/d in the last 3 weeks, Hinch & Thwaites 1990) on milk production in twin rearing ewes and similar responses to supplementation with Norpro (sunflower meal) compared with a maize supplement of equivalent energy content (Rustomo and Hinch unpublished).

Figure 5 Pre-partum lupin supplementation and lactation in crossbred ewes

Figure 6. Prepartum protein supplementation and lactation in crossbred ewes

Conclusions

Without doubt the nutrition of the reproducing female is of vital significance to reproductive success. The studies reported in this paper provide insights into potential areas of loss and potential areas of manipulation which may improve reproductive performance. The strategic use of protein supplements appears to be a relatively cheap means to improving reproductive outcomes at almost all stages of the reproductive process with the exception of embryo survival.

Further studies using CAT scanning technologies will give us greater insights into the importance of body reserves to foetal weight changes and lactation performance. They will also provide a clearer picture of the impact of nutritional manipulations on the partitioning of energy to foetus or body reserves and subsequent incidence of difficult births in maiden animals.

References

- Hinch, G.N., Crosbie, S.F., Kelly, R.W., Owens, J.L. and Davis G.H.(1985) The influence of birth weight and littersize on lamb survival in high fecundity Booroola Merino crossbred flocks. New Zealand J. Agric.Res. 28:31-38

- Hinch, G.N., Kelly, R.W., Davis, G.H., Owens, J.I. and Crosbie, S.F. (1985) Factors affecting lamb birth weights from high fecundity Booroola ewes. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 8:53-60

- Hinch, G.N. and Thwaites, C.J. (1990) Lupin supplementation in late pregnancy: effects on ewe lactation and lamb growth. Proc. Aus. Soc. Anim. Prod.18:489

- Hinch, G.N. Lynch, J.J., Nolan, J.V., Lng, R.A., Bindon, B.M. and Piper, L.R.(1996) Supplementation of high fecundity Border Leicester x Merino ewes with a high protein feed : its effect on lamb survival. Aust. Exp. Agric. 36:129-136

- Koong, L.J., Anderson, G.B. and Garrett, W.N. (1982) Maternal energy status of beef cattle during single and twin pregnancy. J. Anim. Sci. 54:480-484

- Nguyen, X.T.(1996) Artifical Manipulation of oestrus and ovulation in post-partum beef cattle. MAgSci Thesis UNE Armidale Aust. pp 141

- Parr, R.A., Davis, I.F., Fairclough, R.J. and Miles, M.A. (1987) Overfeeding during early pregnancy reduces peripheral progesterone concentration and pregnancy rate in sheep J. Reprod. and Fert 80:317-320

- Robertson, J.A and Hinch, G.N. (1990) The effect of lupin feeding on embryo mortality Proceedings of the Australian Society of Animal Production 18: 544

- Robinson, J.J.(1990) Munition in the reproduction of farm animals. Nutrition Research Reviews 3: 253-276

- Rustomo, B., Hill, M.K. and Hinch,G.N.(1996) The effect of pre-partum protein supplementation on productivity of grazing dairy cows Proceedings of the Australian Society of Animal Production 21:358

- Warrington, B.G., Byers, F.M., Schelling, G.T., Forrest, D.W., Baker, J.F. and Greene, L.W. (1988) Gestation nutrition, tissue exchange and maintenance requirements of heifers J. Anim. Sci. 66:774-782